|

|

Working through the Great DepressionBy: Terri Jo Ryan, Waco Tribune-Herald February 5, 2007 |

Photos

courtesy of the

New Deal Network

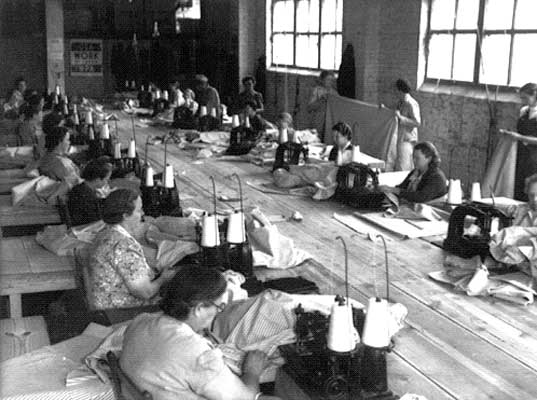

In a mattress-making

project of the

Works Progress

Administration — a federal

New Deal program

of the 1930s

— Waco

workers in this

room are cutting

the bat rolls

for different

size mattresses.

|

Before the Great Depression slammed into Waco following the stock market crash of 1929, the city had been one on the move. By 1930, Waco had grown to 53,848 souls, but hard times undercut the city’s momentum. As prices for cotton and other agricultural products fell and farmers subsequently reduced their spending, businesses in Waco were forced to lay off employees. Ultimately, many shops closed their doors, throwing hundreds out of work. The Texas Cotton Palace Exposition, long a shimmering symbol of the city’s prosperity, even closed its doors. According to regional historians, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs helped to create employment opportunities and infused money into the city. The Works Progress Administration — later known as the Work Projects Administration — for example, established an office in the city and paid for the construction of University High School and other local projects. During the Great Depression, Waco also became a distribution center for the government’s surplus commodities program. The WPA also

put people to

work collecting

oral histories

from friends

and strangers

with great stories

to share. The

Folklore Project

of the WPA Federal

Writer’s

Project — which

ran from 1936

through 1940 — can

be accessed online

through the Library

of Congress.

The online archive

includes some

2,900 documents

representing

the work of more

than 300 writers

from 24 states.

Among the Texans

interviewed were

those old enough

to remember slavery

and pioneer days

in Waco. |

Hardest of hard timesIn the first half of the Depression, evictions uprooted some 60,000 Texas farm families. Driven by necessity, these economic refugees joined a stream of crop-following workers. Rumors of “better pickings” and higher pay caused migrants to flood communities where no work actually existed. In other locales, farmers were begging for “hired hands” to save their crops. The haphazard movement of family labor resulted in conditions that spawned poverty, squalor, health problems and discontent along Texas highways. Tales of starvation and deplorable sanitary conditions in roadside camps shocked the State Employment Service, now the Texas Workforce Commission, into action. The SES encouraged communities to set up camping grounds with running water, toilets and garbage disposal units. Waco and about a dozen other regional centers for migratory labor built these camps — not spectacular lodgings, but a far cry from primitive and crowded mud holes. Waco’s population grew slightly during hard times, and by the eve of World War II, more than 56,000 people called it home. |

|

Sources: Online; www.lib.utexas.edu; http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/wpaintro/txcat.html; Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park, NY | |

|

Return to Moments in Time home page |

|