|

|

‘Crash at Crush’ a calamity beyond hypester’s dreamsBy: Terri Jo Ryan, Waco Tribune-Herald Sept. 15, 2006 |

|

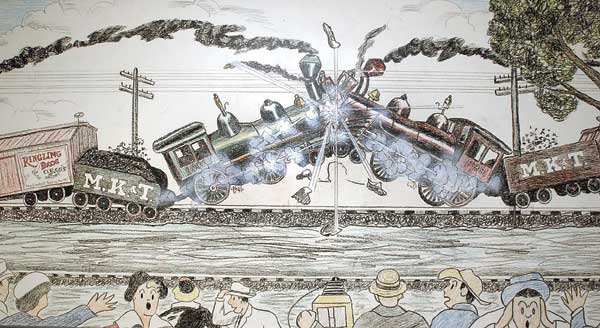

Long before the two-month siege at the Branch Davidian compound ended in chaos on April 19, 1993, and long before the deadly F5 tornado of May 11, 1953, cut a horrific path through downtown, Waco made national headlines for a peculiar kind of catastrophe. On Sept. 15, 1896, in front of an estimated crowd of 50,000 spectators, two trains of the Missouri Kansas & Texas Railroad — better known as the M. K. & T. or “Katy” railroad — were deliberately rammed together for public amusement and private gain. The story of how the “Crash at Crush” came to be is a triumph of hype. William George Crush, assistant to the vice president of the railroad, was a promoter. A disciple of master hokum artiste P. T. Barnum, Crush convinced Katy officials that staging a “monster wreck” of two trains ready for retirement would be great publicity for the line, which was suffering during a nationwide economic downturn. A locomotive crash staged several months earlier by the Columbus and Hocking Valley Railroad near Cleveland, Ohio, had been a great success, he noted, drawing 40,000 spectators. Crush chose a spot in McLennan County on a straight stretch of track on the Katy’s main line about 15 miles north of Waco and three miles south of West for the event. The site, on a special-built four-mile set of tracks, was in a shallow valley with hills rising on three sides, forming a natural amphitheater. Handbills promoting the crash were posted on every available telephone pole along the Katy line from St. Louis, Mo., and throughout Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. Newspaper and magazine ads touted the spectacle, creating buzz months in the advance, from California to New York. Almost every major newspaper provided free publicity through their news accounts of the meticulous planning of the intentional head-on collision. Crush selected two 35-ton Pittsburgh 4-4-0’s of 1870 vintage with diamond-shaped stacks for his dance of destruction. He sold advertising on the sides of the box cars to the Oriental Hotel in Dallas and Ringling Bros. Circus. The Katy, meanwhile, decided not to charge admission to the spectacle. The railroad planned to make its money selling seats on the trains at $2 dollars per round-trip ticket from anywhere in the state to breathless witnesses. Two telegraph offices were constructed for the occasion. Two water wells were drilled at the site, and the railroad hauled in five tank cars of water and several tons of ice for the crowd. The water was piped to the top of a hill on the property, and several hundred faucets placed at convenient intervals. Another more durable building of wood was erected to serve as a temporary jail for all the “bad characters” like drunks, brawlers and thieves that were expected to show up. Three hundred specially-hired policemen were brought in to maintain order. Workmen also constructed a grandstand for officials, three speakers’ platforms and a bandstand. In a tent borrowed from Ringling Bros. circus, food service was offered. A carnival midway sprang up, with medicine shows, game booths, cigar stands and soft-drink vendors to distract visitors while they waited for the main event. Among those in the crowd was a man sent by Thomas Edison to record the event on the Wizard of Menlo Park’s newest contraption, the kinetoscope, or motion picture camera. Texas native son Scott Joplin, the ragtime composer, is thought to have been a witness, for he wrote the piano piece “Great Crush Collision” as a musical tribute. Overlooking it all was a giant sign, informing all comers that this spot of soil was “Crush, Texas.” In 1896, Waco only had a population of 12,000 and Dallas had just 40,000 ? so some historians say that for one day, at least, Crush may have been Texas’ largest city. By 10 a.m. Sept. 15, 1896, a crowd of 10,000 had gathered to swelter beneath the broiling Central Texas sun. By early afternoon, the group had swollen to 30,000. By show time, the clamoring assembly numbered more than 50,000. The collision was initially scheduled for 4 p.m., but since several trains scheduled to arrive with tourists had been delayed, the wreck was pushed an hour. The mob grew restless and only Crush threatening to cancel the event altogether kept the crowd from rioting. |

At 5 p.m. the two locomotives — No. 999 painted in bright green trimmed in red and No. 1001 painted in bright red trimmed in green, each pulling six cars — met cow-catcher to cow-catcher, to be photographed for posterity prior to their destruction. Then the trains backed slowly up the low hills to their starting points. After the smoke-belching behemoths started their final run, the two train crews jumped from the lumbering locomotives to watch the result with everyone else. Maximum speed reached some 90 miles an hour. They set off mini-torpedos laid on the tracks to create small explosions as the trains rolled at full throttle, which spiced up the performance. “A crash, a sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters,” The Dallas Morning News reported in its editions the next day. “There was just a swift instance of silence, and then as if controlled by a single impulse both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half of a driving wheel.” The V.I.P. stand where reporters, photographers and railroad officials and special guests had gathered for a closer look was showered with scalding debris. Official photographer for the event, Jervis C. Deane, of Waco, was hit by a flying bolt that tore out his right eye and embedded several other pieces of metal in his head. J. Louis Bergstrom, another Waco photographer hired to document the event, was knocked unconscious by a plank. The expulsion of shrapnel occurred so quickly, the crowd which stood shoulder-to-shoulder found it impossible to run for cover. In all, three people died and several dozen spectators were injured. Ernest Darnall, of Bremond, was sitting in a mesquite tree and was killed instantly. A heavy hook on the end of a wrecking chain caught him between the eyes and split his skull. DeWitt Barnes of Hewitt, standing between his wife and another woman, also was struck and killed by a flying fragment. Neither of his companions were injured in the debacle. Many others were scalded by steam and burned by jagged, hot shrapnel. A Confederate veteran told the newspapers the scene was like a Civil War battle — people falling all around him. A heavy smoke stack, blasted skyward, fell within the danger area, two heavy trucks weighing a ton each were lifted off the ground by the concussion, turned end over end for three hundred yards. The huge crowd stood stunned for minutes. When all recovered from the shock, they swarmed over the smoking ruins for souvenirs. The injured and the families of the dead were paid by the Katy. Deane was paid $10,000 and accepted a lifetime pass from the railroad as compensation for the loss of his right eye. A few weeks later, he posted a notice in the Waco newspapers: “Having gotten all the loose screws and other hardware out of my head, am now ready for all photographic business.” Crush was fired immediately but quietly rehired a few days later because his trick had worked. News of the “Crash at Crush” earned headlines around the world. The Katy’s business picked up speedily. Crush worked for the company 57 years before he retired. The site of the Crash, about one half-mile west of busy Interstate 35, is just placid farmland now. The last known witness of the now 110-year-old publicity stunt, believed to be Millie Nemecek of West, died in 1983. But the legend of the Crash at Crush lives on, even as the vehicular melee on nearby I-35 sometimes threatens to eclipse it. SOURCES: Railroad and Heritage Museum in Temple; Texas State Historical Association, the Texas Collection at Baylor University, TexasAlmanac.com., Baylor Lariat. |

|

Return to Moments in Time home page |

|