|

|

Residents remember Waco's segregated pastSegregation focus of Waco History Project programBy: Terri Jo Ryan, Waco Tribune-Herald |

|

Although his cooking was fine enough to serve the president of the United States in 1944 when her served as a mess sergeant in Alaska, E.C. Kirkpatrick couldn't eat in the same chow line as his white comrades in arms. Now 81, Kirkpatrick was one of a trio of living history presenter who shared a taste of their lives with an audience of more than 50 Tuesday night at A.J. Moore Academy. As part of the Waco History Project, he and daughter Jewel Lockridge, 56, and fellow Waco native Jean Laster, 50 talked of racial segregation and a period when everyday life in Waco was rife with humiliation. In an interview after his talk, Kirkpatrick said he could recall what her served Franklin Delano Roosevelt that memorable day 60 years ago: "Ham, whipped potatoes, corn, peas and carrots. Kirkpatrick worked in several Waco eateries after the war, including the old Elite Cafe. "I could cook the food, decorate the plate, decorate the salad and serve it all, but if me and my family wanted to eat something I made, we had to go outside," he said, "Now, if I was so bad and dirty and lowdown, why would you want to eat the food I made?" With a wry sense of humor, Kirkpatrick recalled thinking "I must have turned white overnight" when he was finally drafted following Pearl Harbor. For eight months, he said, he had tried to volunteer, only to be told by military recruiters his country "had no use for black soldiers." He and other African-American fighting men rode segregated troop trains and drank from "colored-only" water fountains and endured myriad other indignities while serving the land of the free, he said. Kirkpatrick's recollections of life before the civil rights era riveted black, white and brown listeners at the Waco History Project's Tuesday night meeting. His daughter's story did the same. Back of Buses Lockridge asked listeners, especially children, to put themselves back into the day "when everything was separate for you, based on the color of your skin." She noted how a scene in the movie Ray, the life story of musical genius Ray Charles, showed signs being used to keep blacks on the back of buses. "City buses were that way, but without the signs," she said. "You just knew to move quickly to the rear." As a high school junior, one day in 1964, she boarded a Waco city bus alone in her neighborhood to go downtown to shop. She had seen TV coverage of the civil rights marches and knew blacks no longer were confined to the back of buses. So she paid her fare and sat down on the first seat, directly behind the white bus driver. The driver, furious at her, muttered threats and insults at her, but she held her ground for the duration of the unpleasant 20-minute ride. |

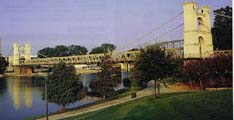

"I knew my rights, that he couldn't make me site someplace else," she said. "But he did have control of the door." When the bus pulled over at Lockridge's stop, the irate driver wouldn't open the front doors and made her walk to the back to exit. Laster, first black female justice of the peace in McLennan County, helped organize an act of civiil disobedience in the 1970-71 school year to protest the LaVega Independent School District's plans not to renew the contracts of several popular black teachers. A high school junior the year of federal court-ordered school integration, she and other black students were forced to shift from G.W. Carver High School in East Waco to La Vega High in Bellmead. Already feeling put out by the transition because they had to give up most of their extracurricular activities, including their award-winning band, Laster said the former Carver students ere further angered by the hostile atmosphere of the city they were bused to and the loss of their own community leaders. Walkout staged Tired of feeling powerless, they decided to stage a walkout. At 10 a.m. one spring morning, Laster said she and about 75 other protesters closed their school books, walked out of class, exited La Vega High and began a five-mile march. The mach took them across the Brazos River to G.W. Carver High and on to Carver Park Baptist Church. Waco hadn't seen many acts of civil disobedience before, Laster said, and the walkout attracted much media attention. "We got results. Our voice was heard," she said, noting that La Vega ISD renewed each coach Clarence Chase's contract for the next year. But another court ruling forced Laster and the other ex-Carver students to once again shift schools the following year. She graduated from Richfield High School, then attended Prairie View A&M University. The Waco History Project seeks to connect people of all ages to the community by telling the story of Waco's diverse past, said John Young board president and events chairman. Young is Tribune-Herald editorial page editor. One of the major goals of the project — a collaboration with the Community Race Relations Coalition, Waco Independent School District, Baylor University, the Tribune-Herald, Historic Waco Foundation and Heart of Texas Regional History Fair — is to provide curricula and other resources for teaching local history in the Waco and surrounding communities. |

|

Return to Moments in Time home page |

|