|

|

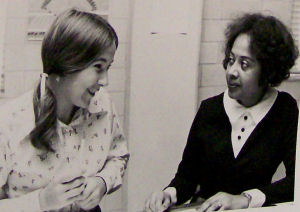

Baylor's first black faculty memberBy: Terri Jo Ryan, Waco Tribune-Herald [click on thumbnail for larger picture] |

|

Vivienne Lucille Malone-Mayes, Baylor University's first black faculty member, came from a "fighting family" of folk who stood up against racial injustices in their day. Her great-great-great-grandfather was Sidney Greene Estelle, who came to Texas from Tennessee soon after the Civil War with his two sons. They moved to the rural McLennan County community of Harrison Switch by 1870, where they were able to buy land to farm. The family grew enough to feed themselves, and made a modest income selling butter, milk and eggs on weekly trips to Waco's old Courthouse Square, an open-air marketplace, she recalled in a 1987 oral history. Her stories were recorded by Rebecca Sharpless, former director of the Institute for Oral History at Baylor University and now an assistant professor of history at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. Sidney's son, Albert Estelle, was the father of Malone-Mayes' grandmother, Meddie Lillian Estelle Allen. Meddie taught school in a one-room schoolhouse in Harrison Switch in order to feed her family after her husband, Jeff Allen ‚€“ himself the descendent of Harrison plantation slaves ‚€“ deserted them. Malone-Mayes was born Feb. 10, 1932, at the South 12th Street home of her aunt, Jeffie Obrea Allen Conner, second wife of the prominent black physician George Sherman Conner of Waco. Jeffie Conner served from 1923-48 as cooperative extension agent for the rural black population of McLennan County, and was a well-known black professional in Waco until her death in 1972 at age 77. Another aunt, Ola V. Estelle Bartlett, an educated woman who taught school, was "an expert" at forging teacher credentials, her niece said, so her kinfolk could get jobs in Central Texas, and was known for agitating for equal pay for black teachers in the 1930s. Malone-Mayes' mother, Vera Estelle Allen Malone, needed bed rest the last five months of her pregnancy because of several miscarriages in her past. Delivered by Dr. Conner and a white colleague, Malone-Mayes was a "blue baby" who survived the dodgy condition. Pizarro Ray "P.R." Malone, her father, married her school teacher mother in 1926. He had worked for Dr. Conner in the 1920s, and was a real estate entrepreneur during the Great Depression, snapping up rental properties that others lost. He later worked for the Urban Renewal Project of the late 1960s-early 1970s. It made for what passed for a comfortable middle-class upbringing in black Waco, Malone-Mayes recalled in her 1987 oral history. She said that although her mother was the one with the formal education, she felt she inherited her math sense from her father. "I give him credit for my mental abilities, whatever they were," she told Sharpless. "He had lived by his wits and he had a great sense of reasoning and how to figure out a problem, any type of problem, quickly." |

The future professor said she first became conscious of race when, at age 3 or 4, she bounded up to a drinking fountain at Montgomery Ward's store in Waco. To her mother's horror, she said, she choose the wrong one, so her frightened mother quickly taught her how to distinguish the words "colored" from "white." Still, she later recalled for Sharpless, shopping was a more pleasant experience for blacks in Waco than it was in Dallas, where they were not allowed to try on dress or shoes and were excluded from shops like Neiman-Marcus. Malone-Mayes graduated from the then all-black A. J. Moore High School in Waco in 1948, at age 16. Starting Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., she earned the BA in 1952 and her masters in 1954, before returning to Waco to teach at Paul Quinn College (1954-61) as chair of the Mathematics Department. Meanwhile, in 1952, she married dentist James Jeffrey Mayes (1922-2002) who owned Mayes Family and Cosmetic Dentistry in Waco. They had a daughter, Patsyanne Mayes Wheeler of Dallas. She also went to Bishop College to teach, 1961-1962, but seeking to expand her knowledge, she applied to take some courses at Baylor University, only to be rejected explicitly on grounds of race in 1961. Many years later, even after having joined Baylor's faculty in 1966 and been named Outstanding Faculy Member of the Year in 1971 by the Baylor Student Congress, Malone-Mayes said she kept the rejection letter as a reminder of her struggle for academic equality. Malone-Mayes, who died in 1995 of a heart ailment at age 63 following her 1994 medical retirement, is recalled by one of her white colleagues as "a great lady at a good time for Texas" who did not shy away from expressing her opinions on injustices around her. "Her eyes flashed if you didn't behave as she thought was right," said Patrick Odell, who retired from Baylor's math department in summer 2001. Odell was a young professor at the University of Texas-Austin in 1962 when Malone-Mayes arrived for graduate studies in mathematics. She was only the second black and the first black woman to get a mathematics doctorate from UT, which had been ordered to desegregate in 1961. In 1966, she became only the fifth black woman in the nation to earn that exalted degree in her chosen academic field. "Those were the years when a lot was changing (at UT). And here comes Vivienne. She was young, attractive and freckle-faced," he recalled in a recent phone interview. "There was a restaurant (Hilsberg's Café) across the street from campus that she wouldn't allow us to go into, because it didn't serve blacks," said Odell, who came to Baylor in 1988. "Those who were real friends to her didn't go." She wrote in 1975 for the Association for Women in Mathematics of her lonely experiences at UT: "I could not enroll in one professor's class. He (R.L. Moore, 1886-1974) did not teach blacks." Other opportunities which would have accelerated her academic career were denied, such as a teaching assistantship. Malone-Mayes wrote that one of her professors, complaining against the civil rights demonstrations in Austin, said to her: "If all those out there were like you, hard-working and studious, we wouldn't have any problems." Her reply? "If it hadn't been for those hell-raisers out there, you wouldn't even know me." The Civil Rights movement was at its height during the years she was in graduate school, 1962-66, and she joined picket lines herself to force restaurants and movie theaters to admit blacks. "Attitudes have changed so much," she said of those days. "When I made a low grade, I felt I'd let down 11 million people. That's a heavy burden. Every professor stereotyped blacks by my performance. You felt like you had no choice but to excel." "She was a treasure to us, and made us better for it," Odell said of Malone-Mayes, whose career he followed avidly through the decades. "Doors opened after that." Additional sources: Handbook of Texas On-line, Association for Women in Mathematics, American Mathematical Monthly. |

|

Return to Moments in Time home page |

|