|

|

When the color line shifted in East WacoBy: John Young, Waco Tribune-Herald |

|

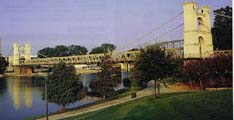

For Waco’s social conditions, one can only attribute human nature. For the lack of directions that make any sense, blame nature. Blame the northwest-to-southeast flow of the Brazos River. Social and directional anomalies particularly pertain to the side of the river opposite Waco’s high-rises and spires. It’s always been East Waco, though more north than east. Directions haven’t changed, but by Waco’s social compass today’s East Waco is far different from yesterday’s. Evident to all is that once upon a time Elm Avenue was a bustling commercial strip. See all the storefronts. Not well understood about a now-racially identifiable area is this: Before World War II the 11 city blocks of East Waco closest to the river were racially identifiable as well. They were all white. All white, right up to the railroad tracks and Garrison Street. Attribute someone who knows: Former city councilman and Precinct 7 justice of the peace Cullen Harris. Now 72, he saw an East Waco that was part white and part "colored," and strictly divided. And he saw the color line move. Actually he was away at Prairie View A&M and in the military when things started to change in the 1950s. A world war that required the fighting might of black Americans helped bring the change about. "We called this the flats," said Harris last week as we drove along Live Oak Street on a block that was all white when he was a child. "Over there, that’s what we called the lsquo;plantation house.’ " At Dallas and Live Oak, it got its nickname for being ornate and brick, something unheard of just a few blocks away in the black part of the old East Waco. There all homes were wood frame. Common were narrow shotgun houses, like the one in which Harris spent most of his childhood. The dividing line between black and white in East Waco? It was a gully, or more accurately where some old railroad tracks used to be, a spot consumed by weeds and hackberry trees, just off Garrison. Interestingly, part of the dividing line was also on Garrison: Paul Quinn College, the nation’s oldest African-American college. For generations a centerpiece of East Waco, in 1990 Quinn moved to Dallas. Today G.L. Wiley Middle School at 1030 Live Oak is predominantly black. When Harris was a child? "All white." It was East Waco Junior High — being in the formerly all-white section of East Waco. In 1957, with population shifts and before desegregation, the school district would pronounce it an all-black school. For junior high and high school, Harris had a long walk — all the way from an apartment just off Garrison Street and across the river to A.J. Moore High School on what’s now University-Parks Drive. As for the delineators of the color line in East Waco, Garrison Street wasn’t the only one. So was "the hill." A hill? Well, Quinn is elevated over the East Waco that terraces toward the river. That’s why blacks came up with "the flats" to describe the area below Garrison. That terrain assumed significance the few times the Brazos flooded, and people in the better homes of East Waco had to vacate, while those in the clapboard up beyond the gully and Garrison Street stayed dry. What changed the face of East Waco? The biggest influence, said Harris, was the war and the prosperity that followed. With the GI Bill, blacks who fought in World War II could attend college. And through New Deal programs they could get loans to own their own homes. After the war, with these changes, when opportunities presented themselves on the "other side" of East Waco, African-Americans were able. Home ownership wasn’t such an out-of-the-question notion. Brick home? Thank you. Social currents the way they are, blacks moved into the 11 blocks toward the river, and some whites moved out. At some point, to Waco’s detriment, the Brazos became a de facto color line. But at one time it was just a river 11 blocks down from the old railroad tracks. |

|

|

Return to Moments in Time home page |

|