|

|

Did lovers really leap from Lovers Leap?By: J.B. Smith, Waco Tribune-Herald |

|

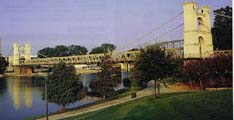

In late 19th-century America, it was nice for a town to boast of a trolley system, gaslights, smokestack industries, colleges and a tuberculosis hospital. But it wasn't quite enough. A real up-and-coming place like Waco also needed a tragedy. It needed a romantic tale to sell postcards, inspire songs and poems and bring tears to the eyes of the corseted ladies. For that purpose the "Legend of Lovers Leap" was made to order. The story of doomed romance was attributed to the Waco Indians, who lived on the banks of the Brazos, and it's set on the tallest limestone cliffs in Cameron Park, still called Lovers Leap . The cliff park is now under renovation, to reopen in time for the park's centennial next May. It was on this cliff that the fair maiden Wah-Wah-Tee, daughter of the chief of the Wacos, stood in the moonlight embracing her secret Romeo, a brave from the enemy Apache tribe, according to the legend. And it was here that the couple, cornered and facing the vengeance and "demoniac yells" of her father and fellow tribesmen, made their fateful decision, recorded by Lamar West in 1912. "Quick Wah-Wah-Tee and her lover, in the last embrace of love and death, sprang from the cliff into the maddened waves below, since which dreadful night it has been known as Lovers Leap ," West wrote in a widely reproduced booklet, The Legend of Lovers Leap. Such is the legend, told with some variations in songs, poems, postcards and Chamber of Commerce brochures over the years. But an authentic Indian legend? Don't bet your tomahawk on it. "I think there is no basis for the legend whatsoever," said Mariah Wade, a University of Texas anthropologist and author whose specialty is the Indians of Texas and the Southwest. "But I wouldn't diminish it too much. I wouldn't discourage those kinds of stories." There's no evidence that the Wacos ever told such a story, and it's not clear how white settlers would have heard it. The tribe, which lived in wigwams and cultivated corn, squash and peaches around the present-day Suspension Bridge, abandoned their village in the 1830s, several years before whites moved in and started their own village. Harassed by the Cherokees, the Wacos moved upriver and merged with other subgroups of the Wichita people, finally moving to a Wichita reservation in Anadarko, Okla. Some Wacos returned to their namesake city in 1912 to be a living exhibit at the Texas Cotton Palace fair, but the Lovers Leap tale was already well entrenched by then, as evidenced by an epic poem written by college student W.O. Blount in the 1911 Baylor yearbook. Of the Texas Indian tales that have been preserved, Wade said, most are moral fables about coyotes and bears and such, not starry-eyed maidens with "dainty moccasined feet" who pass their days weaving flower garlands, as West would have it. And it's hard to imagine a wizened tribal elder indulging in the kind of florid description that West offers: "The birds were singing, the subtle odor of wild grapes filled the air, and the clover spread an azure, fragrant carpet beneath the willow where Wah-Wah-Tee sat and dreamed." The legend may reveal more about the preoccupations of Victorian-era white Americans than the natives they replaced. "Late Victorians could find a way to romanticize anything, to turn the simplest thing into some syrupy sentimental thing," said Tom Charlton, director of Baylor University's Texas Collection, and a doubter of the legend's authenticity. The irony, as Wade points out, is that those romanticizing the Indians as noble savages were the descendants or contemporaries of the Anglo-Americans who killed or exiled most of the Indians of Texas. |

"In the 1800s, at the same time as we are systematically doing Native Americans in, we are also romanticizing them," she said. "We are killing them and calling them dirty scoundrels and savages, but at the same time we are glorifying them and marking the landscape with landmarks of limited connection to reality." Such landmarks could pay off commercially, though. Writing in the June 1919 Harper's Monthly, the writer Ellis Parker Butler recalled his days putting together promotional brochures for midwestern towns. Nine times out of 10, the engravings would include a picture of a Lovers Leap , he wrote. " Lover's Leap was a good card, always," he writes. "There was always an Indian legend, and always the same one. If there was no legend we wrote one, and it was again always the same one. It was always safe to ask where Lover's Leap was when we struck a town, because there always was one if there was a side hill ten feet high. And it was always the same Indian lover and his dusky sweetheart and her cruel father that took part in the ancient tragedy." In fact, the legend can be found in Europe, including British versions from the 17th century. The legend had become a national cliche by 1896, when folklorist Charles Skinner wrote Myths and Legends of Our Own Land. "So few States in this country . . . are without a lover's leap that the very name has come to be a by-word," Skinner writes. "In most of these places the disappointed ones seem to have gone to elaborate and unusual pains to commit suicide, neglecting many easy and equally appropriate methods." Skinner goes on to describe several dozen Lovers Leaps in Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Iowa, New Jersey, Michigan, North Carolina and Tennessee. Many of these stories are suspiciously similar to the Waco story, with the chief's daughter falling in love with an enemy brave. But some offer variations. Sometimes one of the doomed couple is white. Sometimes the girl jumps alone because of the boy's unfaithfulness or because she's facing an arranged marriage. Sometimes she drags him with her against his will. In his 1883 memoir, Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain remembers encountering a variation on the theme during one of his river journeys. A man tells him of how the doomed Indian maiden, named Winona, jumps off a high cliff, while her disapproving parents stand below. She lands on them and crushes them to death but walks away and later marries her love. Twain praises this version as a "distinct improvement upon the threadbare form of Indian legend." "There are fifty Lover's Leaps along the Mississippi from whose summit disappointed Indian girls have jumped, but this is the only jump in the lot that turned out in the right and satisfactory way," he remarks. Then again, the spoilsports inclined to scoff at such tales may be missing out on the fun. As Decca Lamar West writes in The Legend of Lovers Leap: "It is said that sometimes when the spring rains presage a flood, and the moon shines bright; when the mockingbirds make vocal the still night air, one may see on the cliff the flitting figures of a youth and maid. Perhaps it is only vouchsafed to those whose hearts are ever young!" |

|

Return to Places in Time home page |

|