Places in Time

The Mammoth Dig | The ALICO Building | Sandtown | Airfields | Waco's Chalkline | Waco Square | Bridge Street | I-35 | Lake Waco | Calle Dos | Dr. Pepper Museum | Abraxas Club | Carver High | The Reservation | Digging for oral histories | Proctor Springs | White City

Are you from Sandtown?

Rediscovering a

vanished piece of the city

By Terri Jo Ryan, Tribune-Herald staff writer

January 20, 2004

Sandtown, a place that exists only in the hearts and minds of its former inhabitants and their descendants, was brought back to life for an evening through the recollections of some 100 people from the now-defunct neighborhood who gathered for a program by the Waco History Project.

Families with names like Fuentes, Ochoa, Sanchez, Martinez, Vasquez, Ramos, Bravo, Serrano, Torres and Campos were the folks who populated a gritty urban area from 1905 into the 1960s, until the federal Urban Renewal Project wiped clean the area bounded roughly by the Brazos River, Second Street, Jackson Avenue and Interstate 35.

And several of their descendants swapped stories in the parish hall of Sacred Heart Catholic Church on Tuesday, at the invitation of Robert Gamboa and other board members and friends of the Waco History Project. The project is a collaborative effort among several agencies, institutions and individuals to connect people throughout the community by telling the stories of Waco's diverse past.

Gamboa, director of development for Texas State Technical College, as well as a former president of the Waco Chapter of the League for United Latin American Citizens, spent his childhood in Sandtown, so named because if its proximity to the Brazos River.

From grocery stores and auto garages, barbershops and beer joints, an Assembly of God sanctuary to a swinging nightspot and gambling hall called "The Blue Moon," the memories rolled out from a crowd who needed very little goading to get started with the storytelling.

One man recalled watching his neighbors go fishing by casting a line out their bedroom window — they lived that close to the water's edge. One woman said she remembered how 70 families shared a single water faucet under a tree for all their needs. A man told of buying kerosene in bottles, the only way to light the house or heat food at home.

Another woman laughed at the nickname of her street: "La via de las tripas," or " Guts Way," so called because it was the location of a slaughterhouse, meatpacking plant, cowhide tannery and a cemetery.

Many families kept pigs in their back yards, and at least one kept a cow in the front yard. Another woman recalled how much her family struggled to stay afloat economically, even though the rent was only $7 per month on their home.

Society put them there, and poverty kept them there, Gamboa noted. For many of these immigrant families the story of many first generation Americans, he added as soon as they approached affluence, they moved out of the old neighborhood into other areas of Waco. Some of the sturdier homes were re-located to other neighborhoods and given brick facades, he recalled.

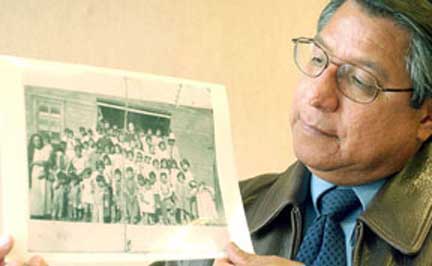

Gamboa said he was pleased to see people hunting through family photos for evidence of Sandtown in their personal past.

"We can document through the families" what may be difficult to uncover in writing, he said.

He also took delight in the appearance of Lenny Englander, whose family owned Sunbright Paper Co. in the heart of Sandtown from 1926 to 1978. Englander elicited roars of laughter reminiscing about Cisto Martinez, a truck driver who seemed to lose his vehicle in the river with some frequency because he'd forget to "park" it with a brick under the tire to keep it from rolling.

"I don't know how many times we had to pull him out of the river," Englander said.

Thomas L. Charlton, director of the Texas Collection at Baylor University, had news for the audience who thought Sandtown had disappeared into the annals of time. Charlton said the Texas Collection is in possession of photographs and records of Sandtown via archives from the Waco Urban Renewal Project, the 20 year, $125 million renovation of the city's urban core begun in 1958 to deal with the problem of inner-city blight.

Federal requirements of the funding called for photographing and recording each property to be removed, he said. Although many records were damaged in a basement flood years ago, almost 80 percent of the records are intact. They have not been processed or indexed yet, but Charlton invited Sandtown's heirs to make appointments to search the files and other archival materials to help them re-create the virtually unknown chapter of local history.

Digging for Oral Histories

By Terri Jo Ryan Waco Tribune-Herald

March 5, 2006

Before the lore of Sandtown slips away, a cadre of Waco historians and helpers came together

to catch some if it in the Sandtown Oral History and Photo Day.

In the parish social hall of Sacred

Heart Catholic Church, scores of professional historians and student history buffs – fortified

by two days of specialized training – came

to learn from the natives and neighbors of those who called the now vanished community their

home.

Sandtown was the gritty urban area that, from 1905 through the 1960s when the federal Urban

Renewal Project wiped out the spot, was located in an area bounded roughly by the Brazos

River, Second Street, Jackson Avenue and Interstate 35.

The Hispanic neighborhood was home to a Mexican-American immigrant community that was served primarily by St. Francis on the Brazos Catholic Church. It had, by many accounts at a preliminary community open house almost 14 months ago, grocery stores, auto garages, a cemetery, barber shops, taverns, an Assembly of God sanctuary and a gambling hall/nightclub called "The Blue Moon." Other businesses of the era included the Sunbright Paper Co. and three meat packing plants as well as one major slaughterhouse.

Sonya Maness, 21, a Baylor University junior majoring in archeology and museum studies, said she is working on a project about the meat-packing businesses of Sandtown. She has identified two of them – Rutland Meat Co. and Waco Packing Co. The whole area was zoned for industrial use, she added. What she found most fascinating in her research was that Rutland in the 1950s was owned by a woman, most unusual for

Baylor cultural anthropology and historical archaeology students conducted the oral interviews and prepared the artifacts from Sandtown past for public viewing.

Jennifer Kidd, 21, a Baylor senior studying archeology and psychology, took charge of cleaning up the artifacts, unearthed in a 1980s dig in the land near what is now the Mayborn Museum.

"It involved a lot of soaking and a little use of a toothbrush," she said of the many bottles (perfume, soda pop, medicine, cosmetics and hot sauce, to name a few) she scrubbed free of dirt and debris.

"There was a lot of stuff I'd never seen before, like a tube of shaving cream," she added. With the help of former Sandtown resident Robert Gamboa, now director of development for Texas State Technical College, she was able to identify a cigarette-rolling device, the busted arm of a phonograph and the handle from an old car trunk.

Gamboa, a former president of the Waco Chapter of the League for United Latin American Citizens, spent his childhood in Sandtown, so named because if its proximity to the Brazos River.

"The amount of broken stoneware and china we have is impressive," Kidd added. While some students focused on taking oral histories from participants, others photocopied documents brought to the event, or scanned old photos into computer images for the Texas Collection, a collection of local history archives at Baylor.

The Texas Collection is the keeper of the archives for the Waco Urban Renewal Project, the 20-year, $125 million renovation of the city's urban core begun in 1958 to deal with the problem of inner-city blight. Collection director Thomas Charlton recalled that federal requirements of the funding called for photographing and recording each property to be removed, so the collection ended up with the photographs and records of Sandtown.

Although many of the records were damaged in a basement flood years ago, almost 80 percent of the records are still intact, but have not been processed or indexed yet, he said. But at a Sandtown community forum 14 months ago, Charlton invited Sandtown's heirs to make appointments to search the files and other archival materials to help them re-create the little-known chapter of local history.