|

|

Black businesses — built from scratchVan Allen |

|

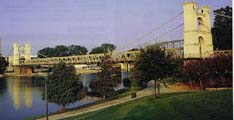

I came to live in Waco in 1985, which some 32 years following the May 11, 1953 tornado which had devastated the city. Shortly after my arrival in Waco, I noticed that the tornado tragedy was revisited each year on, and/or, near the date that it had occurred, via articles in the local newspapers and radio and television presentations. And, I was struck by the significant absence of specific information regarding tornado damages in the black community, and especially in the then-thriving Black business district which was a significant part of downtown Waco at that time. My interest was further stimulated as I initiated discussions with African Americans who were young adults at the time of the tornado. And, I learned from them, among other things the following: 1. African Americans living in Waco at the time of the tornado in 1953 owned a large and thriving business community. 2. this community of businesses was located on, what was identified as Bridge Street, and second and third streets just across from Waco City Hall (one of the buildings that was not destroyed by the tornado). A list of the businesses destroyed by the tornado is recorded in the book African American Heritage in Waco Texas, authored by a black Dentist, Dr. Garry H. Radford (now deceased), published by Eakin Press, Austin, Texas, year 2000. The black-owned businesses destroyed were: the Skylight Tavern, Waco Barber College, Smith Printing Company, (the Waco Messenger newspaper office), Excelsor Life Insurance Co., Simmons Barber Shop, Mayfair Beauty Shop, Henry's Beer Tavern, Squeeze Café, Universal Life Insurance Company, Bridge Street Taxi Company, Rube Livingston Barber Shop, Sally Hughes, Sorrell's Barber Shop, Gen's Shoe Shop, Mecca Drugstore, the offices of Drs. L.R. Adams, M.D. and Dr. W.G. Sorrell, D.D.S., Continental Casualty Insurance Co., Inglehart Appliance and Furniture, Ladies and Gents Beauty Bar, Watch Tower Life Insurance Co., K&K Tailors, Sam Horne Dominoes, Preston Murphy's Barber Shop, Flapper Inn, Jockey Club Barber Shop. Also destroyed was the Conner-Willis Building — containing the offices of R.R. Malone Real Estate, the county agriculture agent), the American Woodman Lodge, and the offices of Dr. Radford. The latter building was one of two three-story buildings owned and operated by black Wacoans at the time of the 1953 tornado. The second building was known as the Fridia Building, which housed the Mecca Drug Store, several medical and dental offices, and meeting space utilized by fraternal and social organizations of the black community. Needless to say, I was immensely impressed by the above-noted achievements on the part of Waco blacks, given the general attitudes and practices of their mainstream white counterparts in their relationships to blacks dating back to the 247 years of their physical enslavement (i.e. 1612-1865), 100 years of experience living within the Plantation system (i.e. 1866-1966) with the latter ending with the advent of the Civil Rights Movement, which was accelerated in the early 1960s. |

More: Bridge Street

During both of the first two eras noted, it is a matter of record that blacks all across the South, including Waco, were both segregated from mainstream America and severely discriminated against in such critical areas as education and the opportunity to access employment where one would receive equal pay for equal work. With Waco blacks having in 88 years (i.e., 1865-1953) attained the commercial achievements referenced elsewhere in this article, the question is clearly raised as the "how did they do this"? After all, their ancestors were officially enslaved until 1865, people who at that time had virtually nothing to start any kind of businesses or purchase land. Yet, during the interim between 1865 and 1953, blacks did do these things. As an example of land acquisitions by blacks here in Waco during the latter noted time, the records show that a significant proportion of what is now Baylor University's campus was owned by blacks. In my dialogue with those black Wacoans who were young adults in 1953, the response to "how" elicited the expressions of the pooling of resources, cooperating and patronization of each others' businesses, and, the patronization of said businesses by the black community at large. The Waco Black Business District had enjoyed the patronage of blacks living in Mexia, Marlin, McGregor, and Downsville, to name several supportive entities.. Sadly, the black respondents who were 50 years old, or younger, had little or no knowledge of this tremendous legacy of successful black owned and operated businesses here in Waco. Such knowledge as how to start over with nothing, as their fore-fathers, just out of slavery did, was not a part of their knowledge. This experience reaffirms the fact that education for different cultural groups in order to be truly relevant, must include the developmental history of said ethnic groups. For all such experiences have within them models of how individuals and groups of culturally indigenous people have, on occasions, "started over." Van Allen is a former administrator at Paul Quinn College. |

|

Return to First Person home page |

|